A look behind the scenes at walks guidebook writing

An insider’s view from 25 years of freelancing

Welcome to my Substack and thanks for taking the time to read these reflections. I am aiming in this post to give you a new perspective on the business of producing walks guidebooks. Maybe the next time you pick up such a publication to purchase or to use, you will see it in a different light.

It occurred to me to cover the subject of writing walks guidebooks after my recent trip to recheck walks in a guidebook that I wrote a few years ago. My last two Substack posts explored different aspects of this trip: Exploring the harsh heritage of Scotland’s far north and Encountering the special wildlife of Scotland’s far north.

I realised that I’ve been involved in this activity for so long that I take the process for granted, but that describing it might be revealing for others. I hope you learn something in this post, whether you read guidebooks or aspire to write them. Or maybe even if you’re a seasoned hand in the field! (We all have our different approaches).

How I started

You will hear a fuller story of why I decided to become a freelancer in a future post. Suffice to say, I was starting from nowhere and my first work came from lots of speculative approaches. Two bore fruit. The editor of the county newspaper agreed that I could write a weekly walk feature for them and a local publisher gave me a commission for a small walks guidebook.

I had used many different guidebooks before that, but never written one (though I did have opinions about what made a good one!). So it was largely a case of learning on the job. I followed this first guidebook with others and kept the newspaper feature going for 10 years (until, after a couple of takeovers, the publication lost all freelance budget). It provided bread and butter (well perhaps only bread), while I became established.

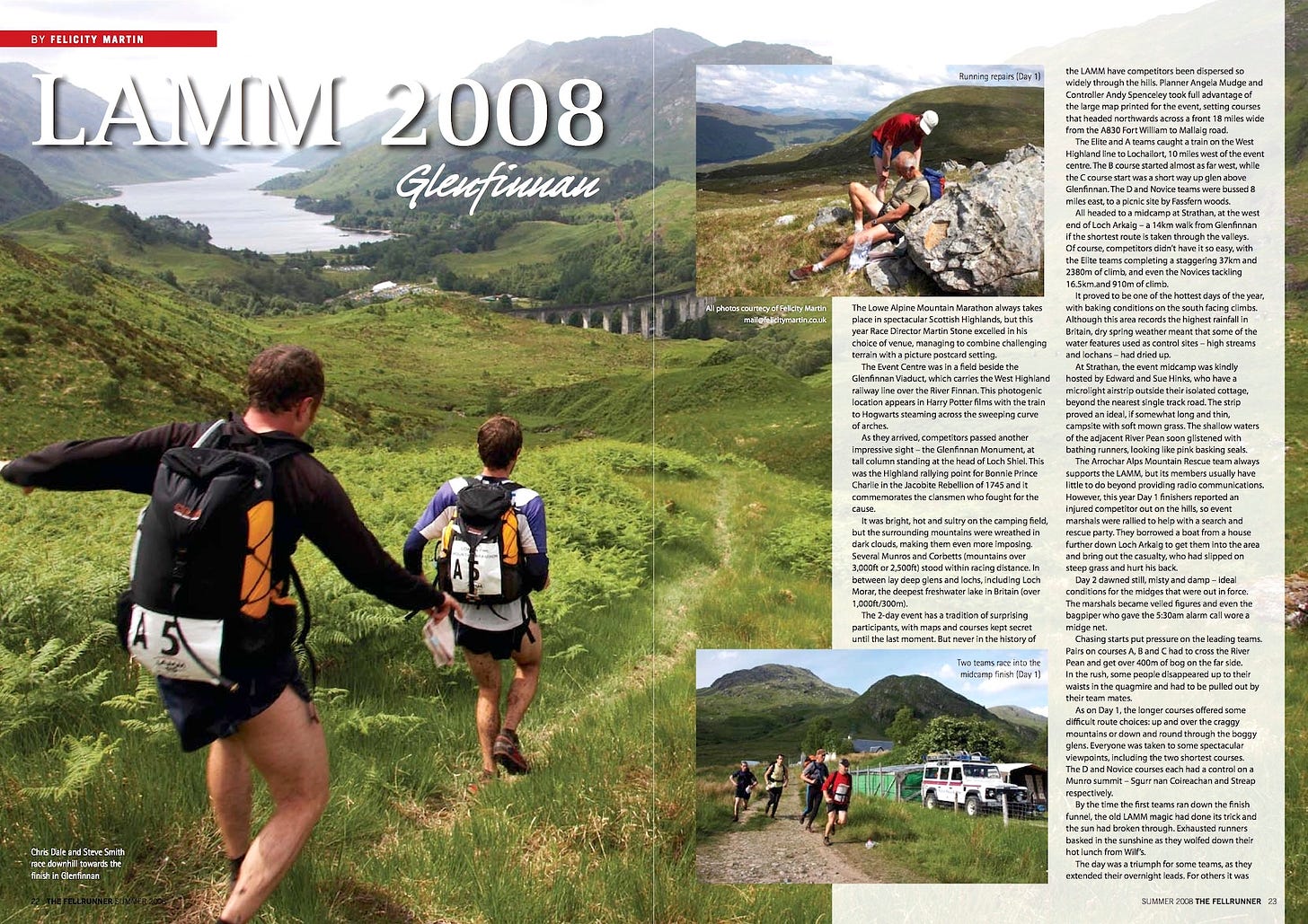

Most of my output was illustrated with my own photographs, so I called myself a ‘writer and photographer’. Early on a colleague persuaded me to join the Outdoor Writers and Photographers Guild (OWPG), and that has been a source of encouragement (and sometimes job opportunities) ever since.

How my work developed

My writing soon diversified into outdoor features for a range of newspapers and magazines, and also promotional writing for organisations such as Forestry Commission Scotland (later Forestry and Land Scotland), tourist boards and nature charities. For several years I planned spring and autumn campaigns encouraging people to get active in Scotland’s forests, through leaflets, website copy and newspaper advertorials.

In recent years the balance of my work has swung in favour of walks guidebook writing again, partly as a response to the decline in print media. Few newspapers make much use of freelancers these days and fees for magazine features have mainly remained static over the years, or even reduced.

It also suits me temperamentally to have a larger piece of work to tackle over a longer period of time. But above all, I enjoy it. Walks guidebook writing is a brilliant excuse to explore places in detail while enjoying time in the outdoors and nature.

The production process

Several people are involved in producing a guidebook. It normally starts with a writer being commissioned by an editor, with whom they agree the scope and content of the guidebook. The idea may have been proposed by the writer or it may be a niche that the editor wants to fill. Most guidebooks form part of a series, so the publisher will probably want the title either to set a new style or to fit into an existing format.

The writer researches the walks on the ground and records the route details. Often they will also be the photographer, so will take images for illustration. They then write the book, draw the route (or tidy up a gps track they have recorded), select, process and caption photographs and deliver everything in a package. Nowadays that is all done digitally, although I remember in the past labelling 35mm slides, putting them in clear plastic sheets with pockets and posting them off.

The editor checks and, as necessary, edits the text (returning to the writer if anything needs clarification) then works with a designer on the layout of the book. Often an illustrator will be used to draw the maps, which, if using Ordnance Survey mapping, requires a paid licence. The writer doesn’t see their work again until proof stage then again when they receive author copies just before publication.

Guidebooks are normally published on a shorter cycle than novels or other books, so the whole process can happen in as little as six months, although a year or so is more usual. That’s not the end of the story, because guidebooks need to be updated periodically so the original author (or another writer) will undertake some checking before a title is reprinted.

My publishing experience

About 10 years into freelancing, I decided that, rather than do one-off jobs for someone else (usually for a flat fee), I would publish my own walks guidebooks and benefit from the income of on-going sales. This was partly because I wanted to produce what I considered an ideal guidebook. But also because I love design and illustration and wanted to develop and experiment with these skills myself.

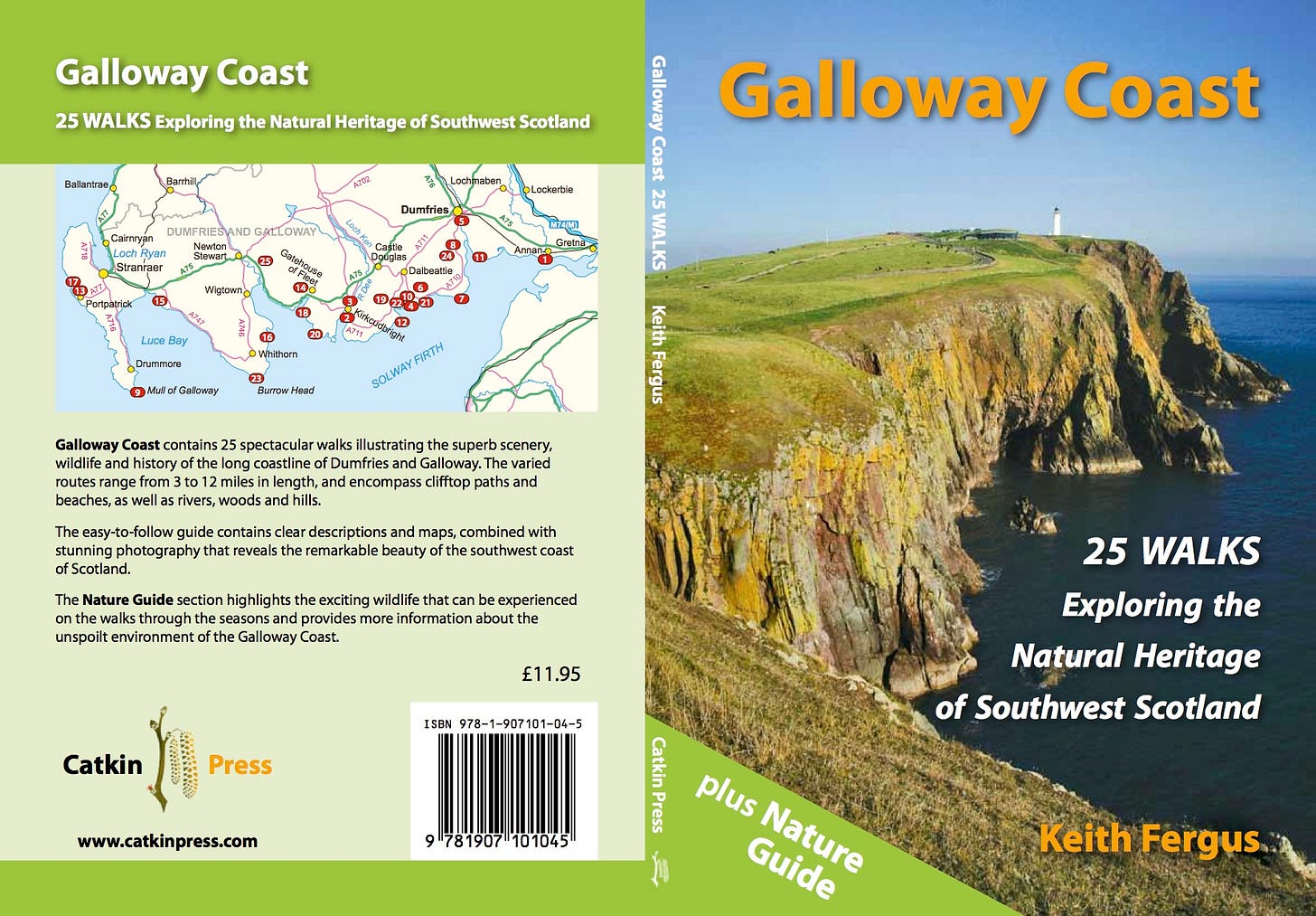

Taking advantage of modern desktop software, I set up an imprint, which I called Catkin Press, and produced five books. Four were slim volumes of Experience Big Tree Country, each with 12 walks around Perthshire, with a focus on its special woodland heritage. The fourth was Galloway Coast, written by a photographer just breaking into walks guidebook writing with an added nature guide to the region by me.

Being a ‘jack of all trades’ type person, I enjoyed the production process and poured intense concentration into producing colourful, inspiring and practical books. Being author, photographer, editor, mapper, designer, proof reader and publisher demanded many different skills and a lot of time, so working 12-hour days became the norm.

What I didn’t enjoy at all was the marketing and selling required to shift the books. I made some brave attempts to gain publicity through launch events and spent days going around local outlets to persuade some of them to stock the book. But all the paperwork and ongoing effort and administration was draining and kept me from more creative work. It was particularly hard to find a distributor as a start up, because they wanted a longer list before taking on a publisher.

The whole thing took its toll, just at a time when I had the added stress of moving home, and I developed a chronic illness. This set me back for five years until it went into remission. I got back into regular work through doing more features for magazines, although in recent years the balance of my output has swung back to guidebook writing. Rather than “doing it all myself”, I now work for other publishers.

Buying a guidebook

My experience from both sides of the publishing industry has taught me what a fine balance publishing a book is economically. The costs involved in producing and printing a title are numerous, but are only one element of the equation. The largest share of the cover price goes to the retailer and, if that’s a greedy one like Amazon, it can be up to 60%. No wonder authors get such modest fees and publishers’ margins can be wafer thin!

Obviously, retailers do have their own costs and overheads, especially if it’s a bricks and mortar bookshop, but sadly capitalist exploitation by big players has unbalanced the industry. If you want to help maintain a thriving book culture, you are best to buy from a physical bookshop or the publisher’s own website.

The next best thing is to use an ‘ethical’ online retailer. These come in different flavours, with some only donating a token amount to the book trade. Others, despite their business names, are owned by Amazon or other big players.

The best online seller I know of is Bookshop.org, “an online bookshop with a mission to financially support local, independent bookshops”. There you buy from the page of a real bookshop (you can select your favourite to support) or the page of an affiliate (usually an author) and a good percentage of your purchase cost (almost all the profit) goes to who you have chosen. If you choose a bookshop they get 30% of the cover price. If you choose an affiliate, they receive a 10% commission on every sale, and a matching 10% is given to independent bookshops.

I have my own affiliate page, which contains most of my recent guidebooks.

Next week I will be looking in more depth at what makes a good guidebook, and exploring practical and moral issues around writing them, using some real examples.

If you have any questions or comments, please share them and I’ll try to take them on board.

Thank you for sharing that, Felicity. I look forward to reading the rest of the series.

That’s fascinating Felicity, thanks for sharing your experiences. What a knowledge of landscapes you must have!